By Gagandeep Nagpal and Himanshu Bakshi

Where do we draw a line?

It is always debated as whether the tax authorities in the garb of transfer pricing can obligate taxpayers to maximise their local profitability in hindsight, by stepping into their shoes to see how a prudent businessman would act in the given facts and circumstances. Over the course of time, the bar seems to have been lowered for tax authorities to challenge commercial expediency on transfer pricing matters. In recent transfer pricing audits, the tax authorities are increasingly questioning the commercial rationality of the business arrangement/transactions, over and above the transaction pricing. One may argue that the commercial expediency depends upon the commercial wisdom of the taxpayer and the tax authorities cannot decide what is commercially expedient for the taxpayer. However, the tax authorities are certainly not precluded from assuming powers against those who attempt to circumvent the law through unacceptable and prohibited means. Therefore, the question arises as to where we draw the line between such power of tax authorities and the commercial expediency of the taxpayer.

Do we have a relevant framework?

It is relevant to refer to Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) transfer pricing guidelines, which assist to provide some guiding principles around this. The OECD has always recommended to respect the transaction as structured by the taxpayer, with two key exceptions, wherein, a business arrangement or transaction could be recharacterized.

First, where a form of the transaction is different from the “commercial substance” (by analyzing the conduct of the parties) and;

Second, where form and substance are the same but the transaction/arrangement, viewed in totality, lacks “commercial rationality” and a transaction is structured such that it would hinder the determination of arm’s length price.

Further, the OECD also clarified that a transaction should not be recharacterised or disregarded just because a transaction/arrangement like one entered by a taxpayer with its group of companies is not found in the open market between third parties. Restructuring legitimate business transactions would be a wholly arbitrary exercise, the inequity of which could be compounded by double taxation created where the other tax administration does not share the same views as to how the transaction should be structured. Current OECD TP Guidelines do not specifically mention the word “recharacterisation” and simply focus on “disregarding” or “non-recognition”.

Interestingly, the revised OECD TP Guidelines post BEPS 1.0 refers to only one of the above conditions (instead of two circumstances mentioned in earlier versions of OECD TP Guidelines), i.e., a transaction/arrangement lacking commercial rationality may qualify for non-recognition or to be disregarded. The only explanation seemingly, though not reflected in the current OECD TP Guidelines, for such a change is that the current OECD TP Guidelines focus on the “delineation” of controlled transactions, and that already addresses the issue of commercial substance.

Delineation means lifting the veil or to understand the real deal in the transaction. The delineation process does not merely go by the form of the transaction as represented in an inter-company contract but focuses on “commercial substance”. The implication of subsuming the “substance over form test” in the delineation process is that it allows tax authorities significant discretionary power and latitude to recharacterize the transaction structure under the garb of delineation.

What is the situation outside?

While there is a plethora of transfer pricing controversies arising out of the issue of recharacterisation across countries, we have attempted to cover the key recent ones which made interesting observations on this issue.

In the case of Glencore Investment Pty Ltd v Commissioner of Taxation of the Commonwealth of Australia [2019] FCA 1432, the Court held that any reconstruction should be limited to the exceptional circumstances referred to in the OECD guidelines. The terms of an agreement cannot be reconstructed to conduct the comparative analysis and must generally respect the actual transaction entered into between the parties.

In Chevron Australia Holdings Pty Ltd v Commissioner of Taxation [2017] FCAFC 62, the Court concluded that a taxpayer cannot write the terms of its loan arrangements with related parties (e.g. to exclude security or a guarantee) and then determine the arm’s length price according to those terms.

In Canada v. Cameco Corporation (2020 FCA 112), the Supreme Court of Canada affirmed the decision of the Federal Court of Appeal which concluded that the recharacterisation provision in the Income Tax Act does not (and is not intended to) prevent MNEs from organizing their activities in a way different from what would be found in entirely arm’s-length circumstances, so long as these situations are priced in accordance with the arm’s-length standard.

In the case of UK vs BlackRock, July 2022, Upper Tribunal, Case No [2022] UKUT 00199 (TCC), overruling the conclusion of the First Tier Tribunal, the Upper Tribunal mentioned that the loan arrangement was put in place with both commercial purpose as well as tax advantage purpose, but for the tax advantage purpose, there would have been no commercial purpose to the loan.

There are many similar interesting case laws on this issue in other jurisdictions as well, especially in relation to inter-company financing and business restructuring. Largely, OECD guidance is being followed to decide on these matters.

Where does Malaysia stand?

After doing a bit of a world tour, let us come back to Malaysia and try to understand what is happening locally regarding this issue. Let us first understand the regulatory framework on this subject matter. Malaysia had an interesting start on transfer pricing as prior to 1 January 2009, there was no specific statutory provision in the Malaysia Income Tax Act (‘ITA’) governing transfer pricing matters. The Inland Revenue Board of Malaysia (‘IRB’) had often invoked Section 140 of the ITA for the years before 2009, a general anti-avoidance provision, to undertake transfer pricing adjustments on transactions not considered to be at arm’s length. In 2009, a specific provision of transfer pricing was enacted via the insertion of Section 140A, which however provided the Director General of Internal Revenue (DGIR) with the power to only substitute prices and disallow interest deductions on certain transactions not considered to be at arm’s length. Therefore, starting with the wider and most powerful provision of general anti-avoidance to regulate transfer pricing, the power seemed to be limited by Section 140A. Although the Malaysia Transfer Pricing Rules of 2012 later empowered the DGIR to recharacterise the transactions in similar situations as prescribed by OECD, however, the Rules cannot stretch the powers emanating from the provisions of the ITA. Realising this legal limitation in invoking the recharacterisation provision, the IRB amended Section 140A and incorporated the recharacterisation provision within the provision of ITA itself effective from January 1, 2021.

In terms of dispute and controversy on this issue, Malaysia’s transfer pricing environment is not isolated. The IRB has been actively invoking recharacterisation provisions primarily in respect of the issues like interest-free advances recharacterised as loans or vice-versa; de-recognition of certain business restructuring; and transactions relating to intangibles, etc. A few cases have already traveled to the Court on this issue, like the case of Malaysia Vs Shell Shared Services Asia Sdn Bhd, wherein the IRB recharacterised the arrangement as intra-group services instead of a cost-contribution arrangement; however, the matter was eventually set aside by the High Court more on procedural grounds rather than on merits.

How can taxpayers mitigate recharacterisation risk?

Considering the business dynamics in today’s world and Malaysia being the go-to destination for various MNEs for expanding their business operations, various restructuring activities are evident on the ground. During transfer pricing audits, it is observed that the IRB has questioned the taxpayers by way of issuing detailed questionnaires to understand the underlying rationale of transactions. If there are no relevant documents available to be placed on record i.e., comprehensive transfer pricing documentation, transfer pricing group policy aligned to agreements, board resolutions, etc., else it can be a challenge for the taxpayer to put up a veritable defence against any recharacterisation attempt by the IRB. From a taxpayer perspective, it is important to follow a proactive approach on the following lines to mitigate the recharacterisation risk:

- Perform accurate delineation of the business arrangement/ transactions as per the revised standards of transfer pricing in the following manner –

- The taxpayer needs to consider whether the written contractual terms are commercially feasible and realistic. If a similar arrangement was to be entered into between third parties, consider whether additional terms would be incorporated or vice versa.

- Critically evaluate the location of the economic activities and avoid possible mismatch with the intercompany agreement. Any loose terms in an inter-company agreement may result in deviation from the actual conduct and may elevate the risk.

- Identify the economically significant risk of the business arrangement/transaction and apply the risk control framework in performing functions, assets, and risk analysis as per the OECD and the Malaysian Transfer Pricing Guidelines.

- The transfer pricing documentation should include the delineation process, business rationale, relevant economic circumstances, and business strategy, before performing any benchmarking analysis. Preferably, transfer pricing documentation should be prepared on an ex-ante basis, rather than on an ex-post basis.

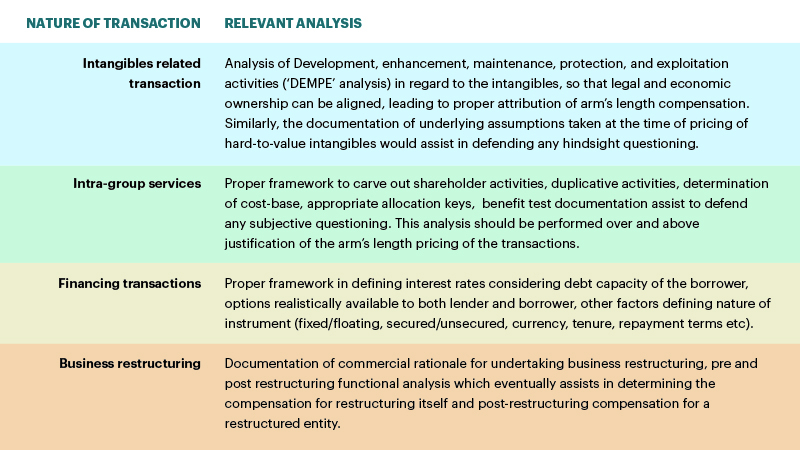

- A few additional analyses (as referred below) in respect of certain transactions which are often at risk of recharacterisation are –

* The above are indicative and not exhaustive; these merely stress the need for relevant analysis and documentation in the context of different types of transactions.

In the end

There is an increasing realisation amongst tax authorities, that transfer pricing provisions (even after incorporating stringent BEPS 1.0 standards) are losing teeth and provide limited assistance in collecting their fair share of taxes. Therefore, along with the implementation of BEPS 2.0 measures, the frequent invocation of recharacterisation provisions by tax authorities may continue as a trend. Taxpayers should be ready with the relevant analysis and the right amount of documentation to defend any recharacterisation challenges.

Gagandeep Nagpal is Executive Director of Transfer Pricing, Deloitte Malaysia.

Himanshu Bakshi is Associate Director of Transfer Pricing, Deloitte Malaysia.

The content in this article are the personal views of the authors and does not purport to reflect the views of Deloitte Malaysia.