By Johnny Yong & Prof Dr. Aiman Nariman Mohd Sulaiman

Members of the accountancy profession are familiar with the assertion that “a distinguishing mark of the accountancy profession is its acceptance of the responsibility to act in the public interest.” This hallmark is stated in the Code of Ethics (the Code) of the International Ethics Standards Board for Accountants (IESBA), which has been fully incorporated into the MIA By-Laws. Nonetheless, within academia and the accountancy profession, this aspect of the Code which is found in paragraph 100.1 of the MIA By-Laws, has been viewed as a challenge to professional accountants (PAs) in performing their role and necessitates further clarification and guidance. Questions commonly posed include: (a) who is the face of the public interest that the accountant is expected to serve? (b) who could possibly be the “other stakeholders” whose interest the accountant must consider? and (c) how does the PA possibly reconcile and balance the divergent interests of all these stakeholders, assuming that they can be identified?

Under the self-regulatory framework that governs the accountancy profession, the Code establishes a set of ethical behaviours which is referred to as the fundamental principles. Under the latest version of the Code, paragraph 100.6 A1 states that “upholding the fundamental principles and compliance with the specific requirements of the Code will enable PAs to meet their responsibility to act in the public interest”. The fundamental principles within the Code are clarified with examples to provide guidelines for PAs in identifying possible scenarios where their judgment is to be applied in an ethical manner.

Currently, the Code does not specify whose interest among the public should be considered or what that interest would entail. Paragraph 100.6 A4 offers some guidance, stating that when acting in the public interest, a PA should consider not only the preferences or requirements of an individual client or employing organisation, but also the interests of other stakeholders when performing his or her professional activities. The term “other stakeholders” is left undefined without further elaboration.

What exactly is public interest?

In June 2012, IFAC issued its Policy Position (PP) 5, A Definition of the Public Interest. The paper aimed at presenting a practical definition of “public interest” that:

- Identifies the public interest as an overarching category; and

- Enables one to assess the extent to which actions, decisions or policies are made in the public interest.

In the said PP paper # 5, IFAC considered the public interest to be the sum of the benefits that citizens receive from the services provided by the accountancy profession, incorporating the effects of all regulatory measures designed to ensure the quality and provision of such services. The “public” in this case, includes the widest possible scope of society: individuals and groups of all jurisdictions sharing an international marketplace for goods and services. All levels of society are affected, directly or indirectly, by the activities and responsibilities of the accountancy profession. This includes all consumers and suppliers in the global economy, regardless of the size of the enterprise or group. The “public” also includes all users of financial information and decision-makers in the financial reporting supply chain: financial preparers, corporate boards, stakeholders, auditors, governments, and financial industries (e.g., banking, insurance, legal, and investment services). It also includes electors and taxpayers, who as citizens of local, regional, and national jurisdictions, are affected by the fiscal decisions of their respective governments for public expenditure and the distribution of public resources.

What then is the definition of “interest”? In the broadest sense, “interest” encompasses all things valued by society. These include rights and entitlements, including property rights, access to government, economic freedom, and political power. An interest is a matter people seek to acquire and control; they may also be ideals to be aspired to, and protections from things that are harmful or disadvantageous to the society at large. In the PP paper, the definition of “interest” is expanded to describe more specifically the responsibilities that PAs have to society. Examples of these responsibilities include:

- Providing sound financial and business reporting to stakeholders, investors, and all parties in the marketplace directly and indirectly impacted by that reporting;

- Facilitating the comparability of financial reporting and auditing across different jurisdictions;

- Reducing economic uncertainty in the marketplace and throughout the financial infrastructure (e.g., banking, insurance, investment firms, etc.);

- Requiring that accounting professionals apply high standards of ethical behaviour and professional judgment;

- Specifying appropriate educational requirements and qualifications for PAs;

- Encouraging governments and public sector organisations to provide their constituencies with sound fiscal information and decision-making; and

- Providing PAs in business with the knowledge, judgment, and the means to contribute to sound corporate governance and performance management for the organisations they serve.

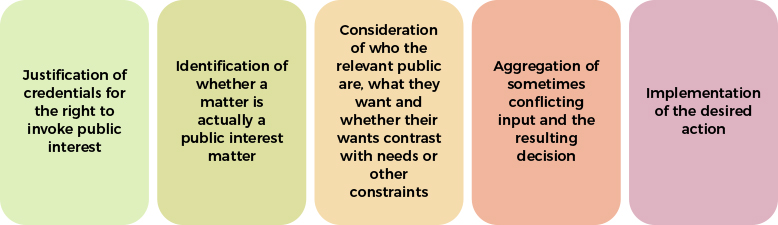

In addition, in 2012, the Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales (ICAEW) as part of the Market Foundations Initiative, issued a summary report entitled “Acting in the Public Interest – A Framework for Analysis”. This report can be seen as complementing the earlier IFAC PP paper # 5. This report acknowledged that public interest is an abstract notion. Asserting that an action is in the public interest involves setting oneself up in judgment as to whether the action or requirement to change behaviour will benefit the public overall – a far greater set of people can then be interacted with directly. It involves interference in people’s ability to go about their own business or sometimes, as a positive policy decision, non-interference in the face of alternative actions. Rather, the summary report is contended to offer a framework that is based on the key issues that need to be addressed by those who are facing the challenge of justifying actions as being in the public interest. The framework in the report covers a number of stages:

This framework will at least guide the PA to act “in the public interest” – by providing an operable framework for asking some thought-provoking questions, although the application may not always be easy.

Enforcement action in relation to the responsibility to act in the public interest

Why is it important to understand the public interest concept in the first place? One reason is the apprehension about liability. The Code pronounces that a breach of the By-Laws due to failure to observe proper standards of ethics and professional conduct could result in disciplinary action before the Investigation and the Disciplinary Committees of the Institute pursuant to the Malaysian Institute of Accountants (Disciplinary) Rules 2002 [P.U.(A) 229/2002].

The significance of ‘acting in the public interest’ and how acting in the public interest should be demonstrated came under the spotlight due to enforcement action against a large firm and its partner and corporate finance expert for their conduct in relation to MG Rover’s case in the UK.

The MG Rover case is unusual in that the FRC (the UK regulator) for the first time directly incorporated the public interest dimension of the work of chartered accountants in the allegations of misconduct. The case was heard by the UK FRC independent Disciplinary Tribunal and subsequently went on appeal to the Appeals Tribunal where the allegation of failure to act in the public interest was set aside.

In the MG Rover case, the Financial Reporting Council’s (FRC) independent Disciplinary Tribunal severely reprimanded the firm involved for its conduct over MG Rover, which went into bankruptcy with debts of £1.4bn and 6,000 job losses. Its report stated that “the public must be protected from misconduct of this nature.”

The misconduct referred to was related to the firm’s role as advisors to MG Rover in two projects (i) Project Platinum which involved buying loan books from MG Rover’s former owner BMW and (ii) Project Aircraft which involved a scheme to transfer MG Rover Group’s tax losses to a company indirectly controlled by the Phoenix Four and enabling substantial payments to be made for the benefit of the Phoenix Four, the accounting firm and the corporate finance expert. The Phoenix Four were actually four directors of MG Rover who had set up a company, Phoenix Venture Holdings (PVH), a private consortium to buy the loss-making British carmaker for a token £10 five years earlier.

The FRC brought 13 allegations of misconduct which centred around both the firm and the corporate finance expert’s (a) failure to adequately consider the public interest before accepting or continuing their engagements in relation to Project Platinum and Project Aircraft and (b) not imposing adequate safeguards to account for conflicts in relation to these projects. At the independent tribunal, it was decided that both the firm and the corporate finance expert were liable for all 13 allegations of misconduct.

However, sixteen months later in January 2015, on appeal by the firm, the Appeals Tribunal overturned eight of the initial misconduct findings including the charge of not acting in the public interest. The Appeals Tribunal acknowledged that the ICAEW Code stated that the public interest should be a factor for accepting any assignment or appointment but disagreed that the public interest is a stand-alone obligation which can be the basis of any charge that an accountant has been guilty of misconduct. According to the Appeals Tribunal, based on the Code, the PAs are required to act with integrity, honesty, objectivity and competence. Any charge of misconduct is based on a failure to demonstrate these four ethical criteria. In the case of the firm and corporate finance expert, the allegation of breach was based on Fundamental Principles 2 which is the requirement to strive for objectivity in all professional and business judgments. If there was a breach, it would have been for failure to act with objectivity. It does not follow that of a failure to act in public interest, but rather that the PAs had acted with a lack of objectivity. Using misleading financial information as an example, the Appeals Tribunal stated that the misconduct in that situation was due to lack of integrity and honesty, and not because the PAs had failed to have regard to the public interest.

An interesting part of the Appeals Tribunal decision was the example given as to what responsibility to act in the public interest does not entail. Acting in the public interest does not mean that the PAs will have to consider political views, philosophical views or the wider public sentiments regarding the morality of a particular business. The Appeals Tribunal gave the example of a takeover bid of a UK business by a foreign company, which could result in the domestic businesses being closed. The Appeals Tribunal was of the view that it is absurd if the PAs should have to consult the government or evaluate if the existing factories could still be continued before accepting the engagement.

Having regard to public interest is also related to other fundamental principles, one of which is the fundamental principle to observe confidentiality. Here, the Code states that public interest is served by observing confidentiality of clients’ information as this ethical principle ensures the free flow of information by the client knowing that there will be no disclosure to any third party. This results in better quality of information and quality of the work performed by the PAs. Clients’ confidentiality is paramount and disclosure cannot be made to others except with the client’s consent or as required by law or regulatory body or association. Public interest here is represented by available laws requiring disclosure of otherwise confidential information. While it may not be in the client’s interest to disclose confidential information, the promotion of compliance with laws and regulations would justify the disclosure.

The application of this fundamental principle has been in the public eye, a case in point being a ‘tax scandal’ involving a major accounting firm in Australia. One of the firm’s former tax practitioners was deregistered as a tax agent for integrity breaches by the Tax Practitioners Board (TPB). The enforcement action was based on an allegation that the tax practitioner had made unauthorised use of confidential information when he was involved in a confidential consultation to improve tax laws for Australia. The government consultancy included new rules to stop multinationals from avoiding tax by shifting profits from Australia to other tax and secrecy havens. The practitioner had shared the information with other colleagues at the firm to aggressively promote the firm’s tax services. The TPB found that the practitioner failed to act with integrity, as required under his professional, ethical, and legal obligations, and terminated his tax agent registration, including issuing a 2-year ban on being a registered tax practitioner. The TPB found evidence of internal firm emails about a plan to use the confidential information and to promote arrangements to circumvent these new tax laws to existing and potential clients. It was reported that the partners made plans around 2015 as to how the information could be used globally. This included contacting several high-profile tech clients such as Apple, Google and Microsoft informing them about the Australian government’s plan and that the firm would be able to provide a plan to help them deal with the pending legislation.

While it could be argued that the practitioner owed a duty to the clients to ensure clients’ interest is protected, this scandal is a good example of the conflict between the practitioner’s self-interest, the clients to whom the practitioner provided the tax advisory services and the public interest. This is also a case involving conflict of interest between a former ‘client’ and the select few current clients that have been given access to the confidential information. In sharing the information, it was likely that the thinking was of the commercial opportunities that the clients would have secured and that the PAs’ responsibility is to promote or protect the client’s interests. However, it is unrealistic to think that the thought of the potential financial benefits accruing to the firm did not cross the minds of those who shared the information or those who let the information be shared. This goes against the standard content of the Code which states that a professional accountant shall not manipulate information or use confidential information for personal gain or for the financial gain of others (as guided by, for example, paragraph R240.3 of the Code). On the other hand, the scandal can also be viewed from the lens of the responsibility to act in the public interest as the subject matter was about the new tax law yet to be passed, which was aimed at increasing the government’s tax coffers in the near future. The practitioners involved were advising companies to sidestep the new tax laws whilst being involved in advising the government to design the law. By giving early warnings, it was reported that the firm netted additional fees and potentially deprived Australia of tax revenue and funds which are important to foster economic growth and development, for social programs and public investment in order to have a prosperous and orderly society.

Is IESBA taking the lead?

The MG Rover case was a possible catalyst for the International Ethics Standards Board for Accountants (IESBA) to consider defining the scope of “acting in the public interest”.

In its proposed strategy and work plan for 2018, the IESBA did mention its intention to explore further into this concept which may “possibly”’ lead to strengthening of the Code. Unfortunately, resource constraints was quoted as a reason for not advancing on this project in the subsequent Work Plan.

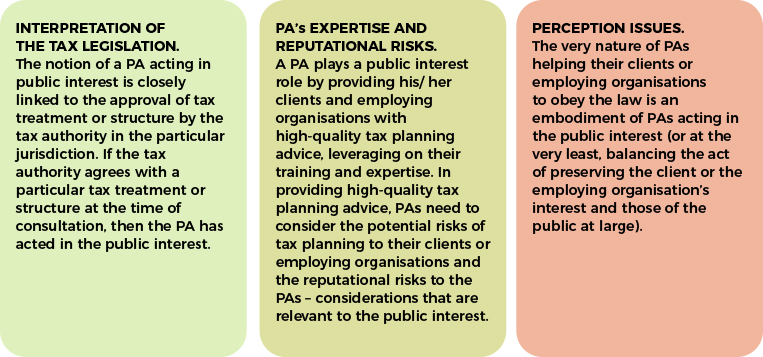

Nevertheless, in February 2023, IESBA released an Exposure Draft (ED) on the potential amendments to the Code pertaining to Tax Planning and Related Services which was subsequently finalised in April 2024. In the explanatory memorandum of the said ED, the IESBA mentioned the role of the PA in acting in the public interest (Pages 11-13). These include some observations such as:

Considering the above 3 scenarios, IESBA eventually decided not to attempt to define or describe public interest given the variety of observations. The IESBA has instead given contextual guidance in the proposed Code (as part of the ED) that explains that an important part of what acting in the public interest means for PAs is for them to contribute their knowledge, skills and experience to assist clients and employing organisations to meet their tax planning goals while complying with tax laws and regulations. In doing so, PAs help to facilitate more efficient and effective operations of a jurisdiction’s tax system which is in the public interest.

Where Do We Go From Here?

It is also worth noting that the responsibility to act in the public interest applies not only to auditors but also to all PAs including the professional accountants in business (PAIBs) and those in academia. External auditors have always been in the limelight whenever financial scandals erupt but the internal controls set-up of organisations is also a significant part of the accounting and reporting eco-system (and well within the PAIB’s domain). One wonders if the PAIBs realise the significance of their responsibility to act in the public interest which could have either prevented or contributed to the financial scandals. Nonetheless, several similar scenarios in other jurisdictions are currently unfolding. As an example, in the UK, Carillion PLC, a now-defunct construction and outsourcing firm is one of them. While there were allegations of external auditors’ negligence, the internal auditor’s failure to identify failings in risk management and financial controls was also a grave cause for concern. This goes to show that the profession as an institution and the members as individuals must be vigilant and consciously reflect on meeting the spirit of the Code continually.

One thing is certain: acting in the public interest is already a given. The ‘responsibility to act in the public interest’ concept underscores the raison d’etre of the accountancy profession. The Code reflect this responsibility. Calls for a better definition could resurface whenever scandals involving accountants and auditors occur and there are cries of loss of confidence in the profession by the public, thereby justifying more regulations. For some, finding a precise definition of the public interest is a holy grail for the accountancy profession. However, there are pragmatic views that even if a definition is provided, the practical application of the public interest concept is difficult due to the extensive list of stakeholders, i.e., the community and the institutions that use reported information generated by PAs or rely on the work of PAs.

The bigger question is whether accountants know when to sum up their moral courage to act in a way to ensure that the trust and confidence accorded by the public and society are maintained, so that the accountancy profession remains relevant. The framework as suggested by the ICAEW and IFAC may not have resolved the elusive task of defining the public interest concept but is still of help to guide the members forward as to how public interest would be served. The approach reminds PAs to avoid merely box-ticking or rubber-stamping and to consider compliance in spirit over the letter of the rules. After all, compliance with the requirements of the Code does not mean that PAs will have always met their responsibility to act in the public interest. At the very least, they should consider consulting with an appropriate professional or regulatory body as mentioned under paragraph 100.6 A3 at a certain point in time – when such a need arises. The PAs, by implementing the outcome of the consultation in good faith, would likely not be faulted for not acting in the public interest.

Johnny Yong is the former Head of the Capital Market and Assurance department of MIA and presently is an Executive Director with the Confederation of Asia Pacific Accountants.

Professor Dr. Aiman Nariman Mohd Sulaiman is a member of the MIA Ethics Standards Board and is a professor of Corporate Law at the International Islamic University Malaysia.