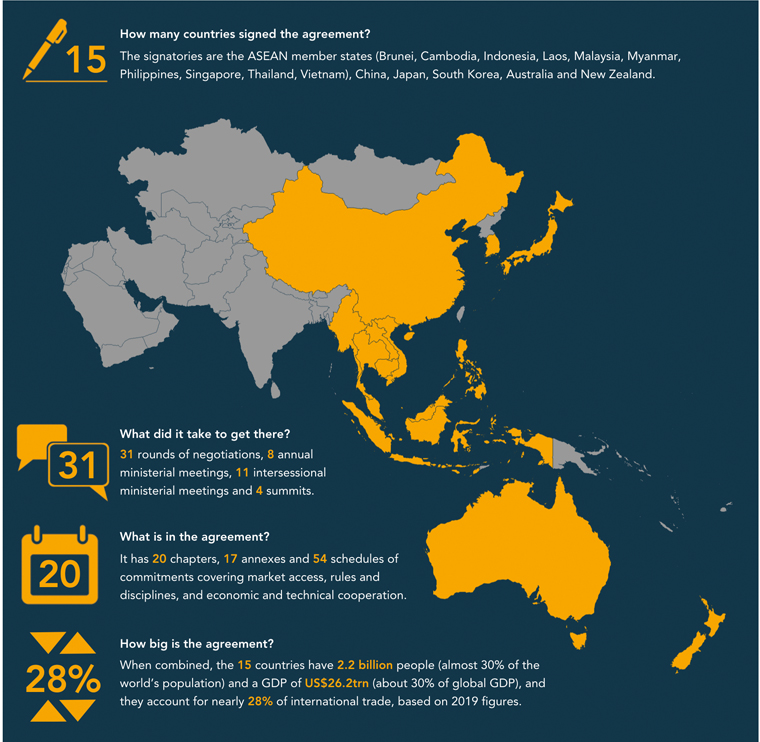

Because of the Covid-19 pandemic, the 15 November inking of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) agreement was a relatively muted affair that mostly played out on screens.

But there is nothing muffled about the response to the sealing of the pact. When 15 countries have banded together to work out, in the words of their leaders, ‘an unprecedented mega regional trading arrangement’, everybody has something to say.

In June 2020, economists Peter Petri and Michael Plummer published the results of computer simulations showing that the RCEP area could add US$209bn annually to global income and US$500bn to world trade by 2030.

Mega bloc

RCEP brings together China, Japan, Korea, Australia, New Zealand and all 10 ASEAN members. That alone is a strong indication of the scale, ambition and dynamism of the partnership.

China and Japan are numbers two and three in the international ranking of economies. They are in the G20 forum, as are Australia, Indonesia and South Korea. And who can dismiss South-East Asia’s tremendous economic potential and strategic importance?

Roughly 30% of the of Earth’s population live in the RCEP zone, which accounts for 30% of global GDP. HSBC has projected that the 15 countries’ share of the world’s output will rise to more than 50% by 2030.

This is also the first time that China, Japan and Korea have all signed up to the same free trade agreement.

Noodle soup

To understand the pact’s rationale, you need to think about noodles.

RCEP builds on and consolidates separate free trade agreements the ASEAN bloc already had with the five other RCEP partners and India. This has created a ‘noodle bowl effect’ of overlapping agreements and troublesome complexity due to differences in rules of origin and technical standards.

This overlap and complexity must be minimised before regional integration can be broadened. RCEP offers a single set of rules and procedures for accessing preferential tariffs across the region, according to a KPMG note published soon after the signing of the agreement.

ASEAN secretary-general Dato Lim Jock Hoi says: ‘The deal will improve market access with tariffs and quotas eliminated in over 65% of goods traded, and make business predictable with common rules of origin and transparent regulations, upon entry into force. This will encourage firms to invest more in the region, including building supply chains and services, and to generate jobs.’

Exit India

There had been several earlier moves that paved the way for RCEP, but it can be argued that the project’s official kick-off was during the 19th ASEAN summit in Bali in November 2011, when the leaders of the association’s member states agreed to a framework for the partnership.

The negotiations were launched a year later, with India also onboard. The initial target was to finalise the agreement by the end of 2015. Predictably, it took longer than expected. Balancing the interests of a diverse group of developed, developing and least developed economies is no walk in the park.

A major hiccup was India’s withdrawal in November 2019. Prime minister Narendra Modi said this was because the agreement did not address satisfactorily India’s outstanding issues and concerns.

The RCEP framework stated that the engagement with the free trade area partners to establish the bloc would be ‘an ASEAN-led process’. The guiding principles for negotiating RCEP required the talks to ‘recognise ASEAN centrality in the emerging regional economic architecture’.

Something for all

Each of the 15 countries expects a net gain from participating in RCEP. Otherwise, why sign the agreement?

All along, the objective was to produce a ‘modern, comprehensive, high-quality and mutually beneficial economic partnership agreement’ that will not only cover trade in goods and services, and investment, but also areas such as intellectual property (IP), electronic commerce, competition, small and medium enterprises, economic and technical cooperation, and government procurement.

Malaysia’s Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI), for example, says RCEP is good for Malaysian companies because it offers market access to a third of the world’s population while facilitating intra-regional sourcing of raw materials at competitive prices.

MITI adds that the partnership encourages the integration of supply chains within the region; promotes greater transparency, information sharing, trade, economic cooperation and standardisation of international e-commerce rules; enables mutual recognition of standards and technical regulations; and provides clarity on the protection of IP rights.

According to the New Zealand government, RCEP will accelerate the country’s GDP growth rate for about 20 years. Once the trade bloc is fully up and running, it says, New Zealand’s annual GDP will be larger by between 0.3% and 0.6%, depending on whether India changes its stance on RCEP.

Australia’s Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade has issued a fact sheet that summarises 12 RCEP outcomes. They range from ‘RCEP will increase opportunities for Australian business to access regional value chains’ to ‘RCEP will support economic capacity building and the capability of SMEs in the region to benefit from the agreement’.

Hoe Ee Khor, chief economist at the ASEAN+3 Macroeconomic Research Office, a regional macroeconomic surveillance organisation, points out that the bloc has been formed at a time when protectionist tendencies have been rising, when economies are finding it harder to generate high growth, and when the pandemic has prompted many countries to think of how to be more self-sufficient. ‘RCEP is a real statement of intent,’ he says.

Opportunities

Because RCEP’s coverage is wider than that of a standard free trade agreement, it presents industries and professions, including accountancy, with novel opportunities and challenges.

The Malaysian Institute of Accountants (MIA) has been an active participant in the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) and sees RCEP as an extension and enlargement of the AEC’s trade cooperation activities. ‘The MIA will continue to nurture the accountancy profession in Malaysia to become the partners to businesses in Malaysia and the RCEP market,’ says its president, Veerinderjeet Singh.

He adds that with RCEP in place, MIA’s advocacy and leadership in professional services collaboration and liberalisation can expand to the bloc’s non-ASEAN partners.

There will also be more room in the region for mutual recognition of professional qualifications and licensing, joint efforts in standards development and convergence, and tax cooperation and harmonisation.

‘The MIA will look for opportunities to collaborate with RCEP countries to advocate for the profession’s role and contribution to the RCEP economic bloc, especially in the context of the digital economy,’ Veerinderjeet says.

Ng Sue Lynn FCCA, head of indirect tax at KPMG in Malaysia, says that, in the long run, RCEP may mean service providers can have greater access to other markets within the free trade zone.

Professional services

The extent to which the RCEP rules for professional services will apply to accountancy is still unknown, and Ng advises accountants to keep abreast of developments so that companies can get prompt advice on how to take advantage of the free trade area’s benefits.

‘Malaysia has lower costs and has already embraced international standards. Its accountants should see RCEP as an opportunity and not a threat,’ she adds.

PwC Malaysia managing partner Soo Hoo Khoon Yean also views RCEP’s arrival as a push for accountants to build their expertise as trusted business advisers.

He says: ‘Covid-19 has already accelerated the need for upskilling as accountants adjusted their work practices and priorities to continue delivering value in a virtual environment. With RCEP, the need for accountants to strengthen their global acumen and technical skills is no longer a choice.’

He adds that RCEP could strengthen Malaysia’s position as a preferred investment destination, pointing to a future where accountants can become a pivotal part of the region’s growth story.

This article was first published in the January 2021 issue of the AB Magazine – ACCA Global.