By Kunal Dutta and Yogesh Mangla

This article is a continuation of Part 1 covering guidance on the transfer pricing implications of the COVID-19 pandemic (the Guidance Note) issued by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD).

In Part 2, we will discuss the remaining two issues, i.e. (a) losses and allocation of COVID-19 specific cost and (b) government assistance programmes. The OECD’s Guidance Note provides much needed clarity to taxpayers who want to take TP positions amidst tax uncertainty arising due to Covid-19.

a) Allocation of losses

The economic downturn caused by the pandemic has severely affected many MNE Groups across the world. These MNE Groups have incurred huge losses primarily due to the decline in market demand, supply chain disruption, and extraordinary or exceptional costs, and these may have significant TP implications.

From the TP perspective, under a typical business situation, limited risk-bearing entities that perform some degree of functions and take insignificant economic risks, are generally entitled to fix routine returns from their Principal. On the contrary, full risk-bearing entities acting like entrepreneurs and that are exposed to all potential financial significant risks, are entitled to residual returns and could have super profits/losses. If we apply the principles mentioned above in the COVID-19 situation, we would need to answer a pertinent question – Should limited risk entities bear losses, extraordinary or exceptional costs incurred during COVID-19?

The Guidance Note has addressed the above questions by discussing the three specific issues, i.e. allocation of losses; non-recurring operating costs arising due to COVID-19 and invoking the force majeure. All these revolve around the concept of accurate delineation of the transactions, third party behaviour, and appropriate documentation.

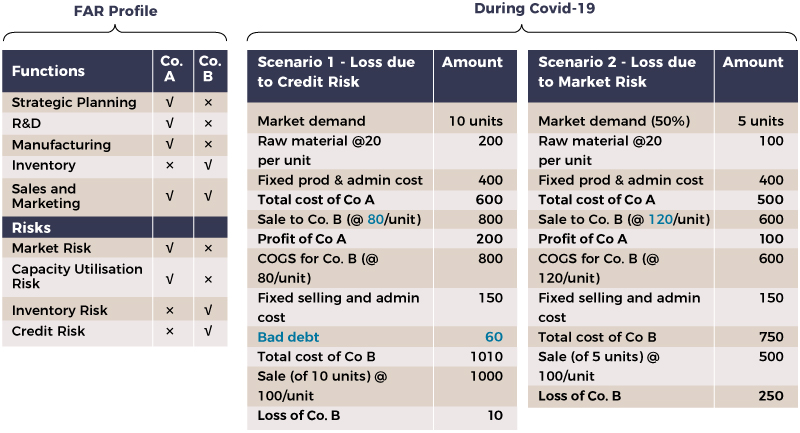

Allocation of losses due to COVID -19 – As each business is unique, it is impossible to set a fixed rule that so-called limited risk-bearing entities cannot incur losses. The OECD TPG states, “simple or low-risk functions, in particular, are not expected to generate losses for a long period”. Therefore, it holds open the possibility that simple or low-risk functions may incur losses in the short run. Accordingly, in assessing whether a limited risk-bearing entity should bear losses or not, it is imperative to first analyse the allocation of risks as per the contractual arrangement and actual conduct of the transacting related parties. Let us try to explain it through the following example:

E.g. Co. B is a distributor of an MNE Group in Malaysia. It purchases goods from its Group’s manufacturing entity, i.e. Co. A, and sells the same to third parties in Malaysia. As per the contractual arrangement, Co. B is entitled to a fixed resale minus base compensation for recovery of its purchase and operational cost.

Based on the above functional analysis, Co. B is only exposed to credit risk. Accordingly, during the pandemic, if there is any default in payment by customers, then Co. B may incur losses due to the materialisation of credit risk (Scenario 1). However, it would not be appropriate for Co. B to bear a portion of the loss associated with the playing out of market risk (Scenario 2). The Inland Revenue Board of Malaysia (IRBM) may challenge the situation wherein before the outbreak of COVID-19, a taxpayer took a position of limited risk distributor to justify its low routine returns. After the outbreak, the same distributor argues to assume marketplace risk. The IRBM could also evaluate any such inconsistent position from the angle of business restructuring – change in risk profile.

Given the current economic environment, there may be changes in contractual arrangements between transacting related parties (such as allowing extended credit terms due to cash crunch). Such amendments are ideally expected to be substantiated with clear evidence that independent parties in comparable circumstances would also have revised their terms or commercial agreements. Herein, taxpayers need to look at various aspects, such as options realistically available to transacting parties, long-run effects on the profit potentials, business viability, if business terms are not revised and any indemnification desired from the arm’s length perspective for any such changes. However, such amendments should be treated with caution (particularly if there is no clear evidence) and well supported by documentation outlining how those amendments are still in line with the arm’s length principle.

Treatment of exceptional costs: Due to the pandemic, entities might have incurred additional costs for their employees’ safety measures or IT infrastructure-related costs due to remote working facilities, etc. It is essential to evaluate whether these costs should be charged back or not; if yes, should there be any mark-up? While assessing how related parties should allocate these costs, an analysis of independent parties operating in comparable circumstances and contractual obligations to bear such costs is necessary.

E.g. Co. A is responsible for the manufacturing of goods and has performed the sanitisation of its plant and machinery. While determining the sales price of goods to Co. B, it is vital to observe the behavior of independent third parties. At the same time, market and geographical conditions do play an essential role. If the taxpayer is operating in a perfectly competitive market, it might not be possible to pass on the additional cost to its customers. However, if the taxpayer operates in a monopolistic or oligopolistic market, it may pass some of its cost on to customers.

Further, there might be a possibility that taxpayers have incurred certain exceptional or extraordinary costs during the pandemic, e.g. internet facility for employees, subsidy to buy furniture, etc., for their business operations. Meanwhile, there might have been a reduction in other costs, e.g. office rent, transportation charges for employees or entertainment expenses, etc. Accordingly, the expenses that substitute for the means of conducting business activities would likely be treated as operating costs.

Finally, while performing the comparative analysis, preference should be given to selecting the TP method, which is less sensitive to the accounting treatment differences. For example, the recognition of the purchase of PPE as an operating cost by the taxpayer and as a cost of goods sold by a comparable company may have a significant impact when computing a profit level indicator based on gross profit and may require a comparability adjustment. However, the application of the transactional net margin method (TNMM) will neutralise the effect of such differences in the accounting treatment and may provide a fair arm’s length comparison.

From the Malaysian perspective, a lot will depend upon the level of disclosure in the comparable companies’ audited financial statements once the data for FY 2020 is published. If all the extraordinary costs are aggregated, then it will not be easy to adjust them out.

Application of force majeure: This refers to the ceasing of contracting parties’ rights and obligations and its legal effect when an extraordinary event beyond parties’ control occurs. The force majeure events might arise in the context of COVID-19 due to lockdowns announced by governments, resulting in the closure of production or retail facilities or complete suspension of intercompany agreement without any obligation on contracting parties. As per the Guidance Note, the contractual agreement between related parties might be the starting point for analysing the TP implication. However, the mere presence or absence of a force majeure clause in the inter-company agreements should not a condition to re-negotiate it at arm’s length basis. The Guidance Note states that it is critical to analyse the independent parties’ behaviour while invoking the force majeure clause or incorporating it in the intercompany agreement.

b) Government Assistance

The nature, duration, and quantum of the grant provided by governments might have an economically significant impact on the controlled transactions, and consequently, TP implications may arise.

Accordingly, the Guidance Note suggests that it is critical to evaluate how the government grant is economically relevant to the controlled transactions. A direct government grant in the form of a direct subsidy or financial support may be more economically relevant than an indirect government grant in the form of infrastructure or waiver of taxes for the short-term. While evaluating, taxpayers need to consider the following. How is the government’s assistance advantageous to the business? What impact does it have on their revenue or cost? To what extent is the benefit passed on end-customers? If the benefit is not passed on to end-customers, how would independent parties allocate such benefits among themselves?

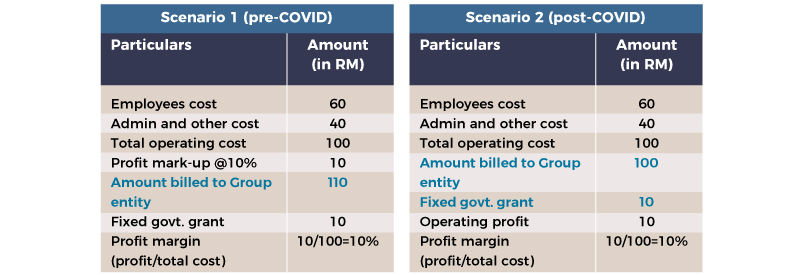

The example below explains the impact of a government grant on the controlled transaction:

Co. A is operating as a captive service provider on a cost-plus 10 per cent basis to its Group entities. During the lockdown, Co. A received a grant of RM 10 from the government.

In scenario 2, ideally Co A should charge a mark-up of 10 per cent. However, due to government grants and even without charging mark-up, Co. A’s operating profit margin is 10 per cent; thus, the profit margin of Co. A apparently seems at arm’s length and the entire benefit of government grants passes on to the group entity.

The Guidance Note suggests that the receipt of a government grant may minimise the impact of economically significant risks during this pandemic; however, it will not alter the allocation of risk under a controlled transaction for transfer pricing purposes. Co. A received the grant from the government; therefore, Co. A should charge its Group entity on an arm’s length basis or follow the same behaviour as it might have followed while dealing with third parties.

Besides, in the Malaysian TP scenario, insufficient data of comparable companies in the public domain is another hurdle while performing comparative analysis. Even though the taxpayers and comparable companies might be engaged in similar business operations, the kind of government grant received by both of them, its quantum, and accounting treatment might result in material differences in the profit margins. Accordingly, caution should be exercised while applying TP methods, specifically in the case of a one-sided profit-based approach, i.e. TNMM which is quite prevalent in Malaysia. Appropriate accounting adjustments should be made to carve out the differences of government grant received by the taxpayer vis-à-vis comparable companies.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic has stirred up the tax environment. By issuing its detailed Guidelines, the OCED has tried to address the key TP concerns caused by the current pandemic. However, it will be interesting to see how flexible the IRBM would be in adopting these guidelines during TP audit proceedings for the period impacted by the pandemic. Simultaneously, the taxpayers should prepare comprehensive TP documentation with proper documentation and evidence of COVID-19 impact on their business as prescribed under the Guidance Note, especially if they have low margins. Any change in pricing policy or business arrangement with related parties should be well documented with its rationale. The recent changes in the TP penalty provisions and shortening of duration to submit TPD (within 14 days) demonstrate the IRBM’s expectations on TP compliance from the taxpayers. Accordingly, without waiting for an audit notice from the IRBM, taxpayers should maintain comprehensive TP documentation on a contemporaneous basis and proactively engage in discussion with their tax agents or with the IRBM. Further, the taxpayers may consider opting for a dispute avoidance mechanism, e.g. voluntary disclosure or APA based on their position. Lastly, the IRBM may issue its own guidance as a written position paper to provide certainty in Malaysia for Malaysian taxpayers.

Kunal Dutta and Yogesh Mangla are senior managers in Deloitte Tax Services Sdn Bhd who have been practicing transfer pricing for over ten years. The opinions expressed above are the authors’ alone and do not reflect the opinion of any institution or organisation to which the authors might be affiliated, whether in the past, present or future.