By Hayley Teo

Insights from Roland Berger’s latest study “Bridging the digital divide: Improving digital inclusion in Southeast Asia” show that digital technology has been increasingly embedded in every part of the economy and individuals’ livelihoods. This is especially apparent in the recent COVID-19 pandemic, with digital tools replacing physical interactions and transactions.

“In Southeast Asia, however, there are approximately 150 million adult individuals or 31 per cent of the adult population that are still currently digitally excluded because they lack access to communication technologies or have low levels of digital literacy,” says Mr Damien Dujacquier, senior partner and co-author of the study.

Disabilities, illiteracy, age, wealth, concentration of economic activity in urban areas and enterprise access to capital are common factors that create this digital divide.

Digitalisation, including the automation of factories (Industry 4.0), has transformed the economy and dynamics of global industries, including in Southeast Asia. Digital skills and capabilities are now fundamental to successful participation in societal and economic activities. If the digital divide is left unaddressed, large parts of the population will miss out on the opportunities that digital technology presents.

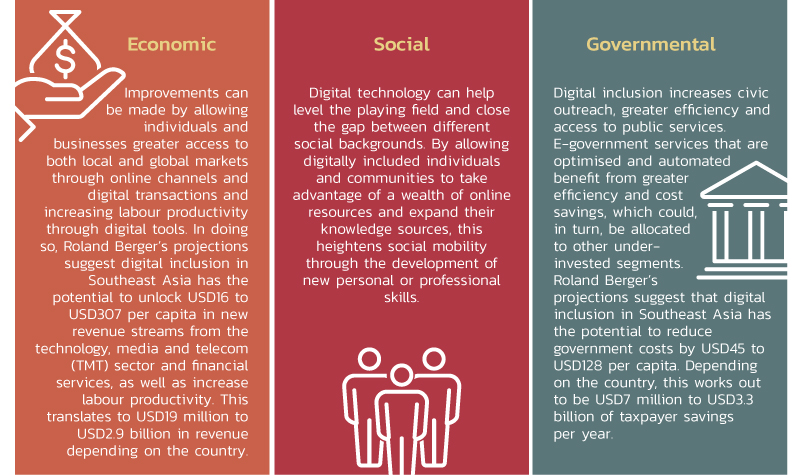

Benefits of digital inclusion

“At least USD15 billion in revenue and savings per year can be unlocked in Southeast Asia by bridging this digital divide,” states Mr John Low, senior partner and co-author of the study. Emerging nations cannot afford to ignore the digital sector if they aspire to increase their share of global trade. These impacts can be measured across three areas:

Key findings in Southeast Asia and Malaysia

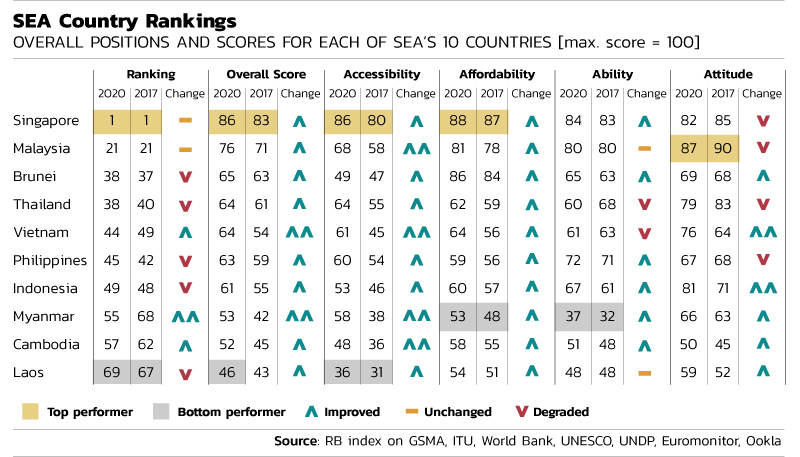

In Roland Berger’s Digital Inclusion Index (RB DII) which measured the level of digital inclusion in countries based on four key levers; accessibility, affordability, ability and attitude, Southeast Asia ranked fifth out of seven global regions. This is due to low scores in the affordability and ability levers. The cost of data and telephony and Information & Communication Technologies (ICT) tools such as smartphones and computers remain relatively expensive for the largely low-income populations of many of Southeast Asia’s emerging nations. Similarly, levels of education and digital literacy in the emerging areas of Southeast Asia also lag behind the global average. But Southeast Asia is stronger when it comes to accessibility and attitude, where its scores are at or above the global average. Recent infrastructure developments have supported greater smartphone use in the region, for example, and a young demographic has driven enthusiasm for technology and hunger for greater digitalisation.

Malaysia is a forerunner in Southeast Asia, ranking 2nd behind Singapore and ranking 21st on the global scale.

Malaysia’s score in attitude surpasses Singapore and is highest in the region. In a Randstad survey, 70% of Malaysians are proactive in learning about technologies that will disrupt the workplace such as AI to maintain their employability, and 85% also believe that digital transformation will require different skills from what they currently possess, but they believe that these changes will invite new opportunities. Malaysia also performs well from a capability standpoint, evidenced by the government’s efforts in proactively injecting digital skills into the curriculum. This emphasises that Malaysians are willing, ready and capable of embracing the digital economy.

Malaysia has sustained its digital growth by boosting accessibility. Its MYR22 billion (USD5.4 billion) National Fiberisation and Connectivity Plan (NFCP), and the rollout of enhanced 4G connectivity by TMT companies, are expected to further increase this. However, quality remains an issue. While the policy and infrastructure dimensions score well at 96 and 73, respectively, the broadband quality score is still very low at 45. This poor performance is a drag on its efforts for greater digital inclusion.

To successfully achieve nationwide participation in digital transformation would require greater availability of consistent and high-quality infrastructure and overcoming financial cost barriers and digital literacy, especially amongst certain demographics in the society including low-income households, rural and aging populations.

The government can help ready the nation’s digital workforce for the global stage. With remote and virtual workforce becoming a norm, Malaysia can build a digitally capable workforce that has access to markets both locally and globally through online channels and digital transactions. Since the scope for digital work is no longer limited to the office cubicle or even within the nation, this offers Malaysians the opportunity to access remote work from abroad. The Malaysia Digital Economy Corporation’s Global Online Workforce programme empowers Malaysians to pursue such an option, through a series of classes and mentorship.

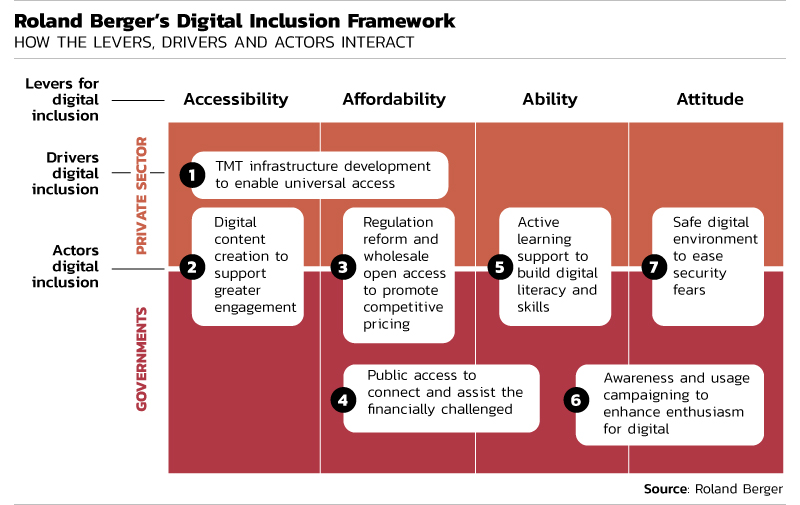

Improving digital inclusion requires private sectors and governments to work hand in hand

Roland Berger devised a framework to improve digital inclusion based on seven drivers shown in the graphic above. However, achieving these drivers require strong involvement of and collaboration between the private sector and governments to support the four key levers.

Whether with network providers, e-commerce retailers, digital banking services or social media, most end-user engagement involves commercial players. Therefore, the private sector needs to play its part in offering services that are viable and secure for underserved markets if digital inclusion is to be enhanced. For example, service start-up apps demonstrate their ability to promote digital inclusion by integrating individual service providers and SMEs into their platform, thus expanding digital inclusion.

Expanding digital inclusion often requires governments to take the role of chief initiator. Some countries have set up a national agency to oversee the management of digital initiatives involving multiple facets, from land development, community development, education and manpower development to economic development. This could be in the form of a digital inclusion council. Over time, as digital inclusion grows, the council’s purpose may evolve into achieving the next step in the ongoing process of digitisation such as digital readiness or Smart Nation.

Governments can also take the lead in driving digital inclusiveness. A popular strategy is to do this through e-government programmes, in which government services are digitalised. By exposing the population to digital interactions as a by-product of consuming government services, e-government can build greater accessibility, ability and attitude. Examples of countries with strong e-government programmes include Singapore, Sweden and Estonia.

Digital inclusion is the way forward to creating more enabling and competitive societies, propelling them to greater heights in the future.

You can download the full study here: https://www.rolandberger.com/en/Insights/Publications/Bridging-the-digital-divide.html

Hayley Teo is the Regional Marketing & Communications personnel from Roland Berger. Roland Berger is the only leading global consultancy of German heritage and European origin. The consultancy is an independent partnership owned exclusively by 250 Partners.

This article is part of a knowledge sharing series under the MIA Digital Technology Blueprint, which can be accessed here.